- Published on

Worrisome Signs of Wilting in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 3

- Authors

- Name

- Katie Quill

Poppy Playtime: A Profitable Controversy

Poppy Playtime has been an indie game darling since the release of Chapter 1 in October 2021. It tells the story of an ex-employee of the Playtime Co. toy factory returning to investigate the disappearance of every worker in the building ten years prior... only to find themselves trapped in the building with hostile living toys. The game is immensely popular with online content creators, with an endless stream of Let’s Plays and other fan content even three full years after initial release.

Both the game and developers have faced their fair share of backlash, beginning with the choice of genre. Originating with Five Nights at Freddy’s in 2014, “mascot horror” is characterized by the perversion of family-friendly mascots in the vein of Chuck E Cheese or Ronald McDonald. Poppy Playtime specifically (as a high-profile example) receives a barrage of criticism from folks who see the game as primarily a vehicle for merchandise rather than a satisfying product on its own – a spin-off free-to-play game, potential film adaption, and rush for licensed toys give critics seemingly endless ammo.

The most talked about controversy happened in 2022, when developer Mob Entertainment (a company with more than one subsidiary, making me question just how indie Poppy Playtime can even be anymore) released a set of NFTs based on the IP. A 2022 Screenrant article elaborates on further scandals – Mob Entertainment has faced somewhat shaky allegations of plagiarism, poor working conditions, and bullying. I can’t say for sure that Mob Entertainment isn’t guilty of something worth blowing open, but evidence of that is beyond the scope of this article even if I find their behavior to be, at minimum, unprofessional at times.

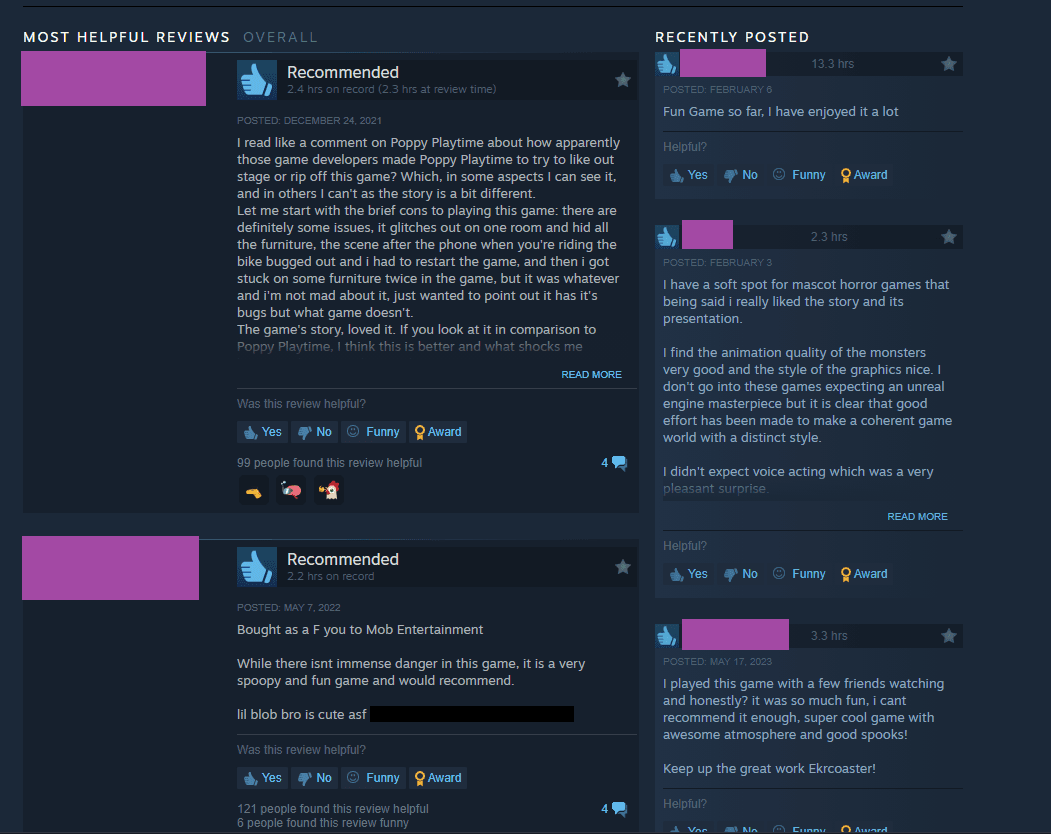

To expand on the only plagiarism allegation I’m aware of, YouTuber and solo game developer EkrCoaster claims that, in addition to sending him harassment over YouTube in the years before releasing Poppy Playtime, the founders of the Mob Entertainment also plagiarized his own indie game Venge, released initially in 2020 and following a similar episodic update schedule. Curious, I nabbed Venge at $1.99 US and booted it up for about thirty minutes (I am a bona fide coward who will jump every time their shadow makes a loud noise). I get the comparison – a facility based around marketable characters disappears overnight with hundreds of staff who are never seen again? Given the personal history between EkrCoaster and the founders of Mob Entertainment, the allegations make sense even if it’s hard to call this plagiarism.

Venge surprised me by feeling less like a carefully-structured corporate product and much closer to some of the better Five Nights at Freddy’s fan games. It reads as a passion project from someone who loves the genre, with strong atmosphere, scares, and a few laughs right off the bat despite a slow build in the early game. I assumed that the 93% positive review score on Steam was rooted pretty intensely in a parasocial hatred for Poppy Playtime, with multiple of the most highly-rated reviews (all several years old now) specifically mentioning buying the game as a symbolic protest against Poppy Playtime. But honestly? I get it; I like the game too. While updates are scarce, the developer has not given up on it. It’s not a masterclass in game design the way some indie studio or solo developer games are, but the love is there.

I can’t say the same thing about Poppy Playtime. Whether or not the game is rooted in a stolen idea, the real threat to the series is its own poor writing decisions that don’t fit the polished high-budget presentation. With chapter 3, the game feels more derivative and lackluster than ever before in a way that desperately calls for a change in direction.

A Lukewarm Defense of the Franchise

If we focus on just the game as a product, I have always been quick to defend Poppy Playtime as arguably the best of its contemporaries as far as mascot horror goes. Far from being a walking simulator with maybe a purchased gameplay asset or two shoved in awkwardly, the game does have a central “Grabber” mechanic that evolves over the course of each episodic chapter, giving each one a unique feel and living up to the claim of being a “horror/puzzle adventure” as the Steam page promises.

Let’s compare the game to what the genre originator was doing at the time. Five Nights at Freddy’s: Security Breach had a number of design problems that stem primarily from a slapdash creative vision by a company that was in way over its head. At several points in the game, you the player are prompted with a Simon Says mini-game that functions exactly like the classic Simon toy you can find at your local department store right now. It’s short, annoying, and feels out of place. Chapter 2 of Poppy Playtime, released five months later, similarly incorporates a Simon Says mini-game that utilizes the Grabber, is incorporated into the story of the chapter, and escalates quickly into an over-the-top parody of itself that I ended up giggling with joy at the absurdity of it all. I cannot look at that segment of Poppy Playtime without thinking that they took the idea as far as it can possibly go. I can’t look at the same segment in Security Breach without asking why they included it at all; maybe Mob Entertainment felt the same.

There are minor elements worth acknowledging, too. The game has good atmosphere and set design even if the environmental puzzles strain suspension of disbelief. They feel out of place in a factory, but back in the day when we had celebrity level designers like American McGee and John Romero, this factory would feel right at home. Meanwhile, the story feels well-planned, with strong foreshadowing and thematically consistent writing throughout; going back to earlier sections is a treat because what you’ve learned adds context, and the moment-to-moment writing specifically is very engaging. And while the characters feel designed with an eye toward merchandise, it would be hypocritical of me to to criticize the game for thinking about merch when every YouTuber and web show is constantly pushing out their own iconic merchandise, sometimes very expensive and seemingly directed at a younger, more impressionable demographic; I have never been a huge fan of how hard Game Theory pushes its merch, for example. Series such as Helluva Boss and The Amazing Digital Circus are aimed at older audiences, but physical products are still a very important part of their business strategy and seemingly gets a pass where indie games (though again: multiple subsidiaries) that fall short of universal acclaim do not.

Regarding audiences, I wasn’t able to find any confirmation about the intended demographic for Poppy Playtime. It does not have an ESRB or PEGI age rating, and sites advising parents on age-appropriate games range in recommendations: some suggest eight and up, others sixteen and up. I bring this up because while the game is not particularly scary for adults, who make up the majority of games discussion online, it doesn’t strike me as any less frightening or grotesque than kid-oriented horror from my own childhood such as Goosebumps or Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. At the same time, I would have liked to know if that was the intention; what constitutes valid criticism changes slightly depending on if a piece of media is meant for kids or adults.

June 1, 2025: This is actually untrue; I didn't know that PEGI and the ESRB had websites I could search directly. The first three chapters of Poppy Playtime have a collecting PEGI 16 rating and a T for Teens ESRB rating. Obvious oversight on my part; chalk it up to me not having a lot of research experience.

Wearing Inspiration on your Sleeve

Chapter 3 of Poppy Playtime released in January 2024, 16 months after Chapter 2. This long wait is reflected in a quality update with a longer playtime and more impressive art design, but again prompts the question of whether this really is a series for children, who have a tendency to outgrow a franchise in just a few years (especially if there aren’t frequent updates); even I had to go back and watch a bunch of old footage just to remember all the important story beats and foreshadowing, assuming I even got it all. It is also $5 US more than Chapter 2; understandable given the amount of effort that went into the game, but are players willing to keep paying this much or even more for future updates? Given the long production time, could Mob Entertainment realistically price new chapters lower if they still want to make up their development costs? Perhaps they have made an official statement about their intent on how to price new Chapters moving forward, but it can be hard to know for sure when all communication is decentralized across multiple social media platforms.

The Steam page for Chapter 3 sits at 85% positive reviews at time of writing, not overwhelmingly positive but generally favorable. People dislike the boss fight and lack of story progression, but a lot of negative reviews specifically mention bugs that the developer has taken steps to address. There doesn’t seem to be much dissatisfaction from the reviewers regarding design choices.

When Chapter 1 released (14 months after our new favorite indie darling Venge), the comparison to Bendy and the Ink Machine was immediate – Chapter 1 was a short free mascot horror experience invoking a mid-20th century aesthetic where a former employee of a company returns to find monsters where they’re looking for people. Chapter 2 even includes a cameo from YouTuber Jacksepticeye just as Chapter 2 of Bendy does. It is perfectly okay to be blunt about your inspiration if your own identity shines through, and Poppy Playtime has nothing if not a clear identity. This is why it ultimately doesn’t matter if the developers took inspiration from Venge or not: anything short of brand or copyright infringement isn’t going to make much of a difference in a genre with such well-defined conventions that creative teams can spin in unique ways.

But footage of Chapter 3 soured that disposition for me a little. Perhaps my sensibilities as a writer had changed in the more-than-a-year between updates; had I become too cynical? I found myself asking “Why are they doing this?” far too often for me to feel fully immersed the way I had in previous chapters despite having been aware of the comparisons to Bendy and FNAF.

In his Let’s Play, Jacksepticeye notices a new Bioshock feel to the game, which is immediately reinforced as the player gets on an elevated tram that takes them to an immense structure while the voice of the founder on a black and white TV explains his philosophical motivation for creating the environment you’re about to enter. The player is introduced to an underground orphanage eerily reminiscent of the neighborhood set in My Friendly Neighborhood, another highly-acclaimed mascot horror title that came out while Chapter 3 was in development. Over the course of the story, the player discovers hints that the children living in the orphanage were secretly being experimented on against their will, knowledge, or consent – very evocative of The Promised Neverland, a show with a highly-acclaimed first season.

None of this is damning on its own. I joked earlier about the developers intentionally taking the Simon Says mechanic from FNAF: Security Breach, but part of establishing an artistic identity is taking inspiration from many sources both within and without your chosen genre. Poppy Playtime is by no means a ripoff of any of these properties; it is too distinctly itself. Even though Chapter 3 starts with a reference to the famous trash compactor scene from Star Wars: A New Hope, it would be silly to act like they had done something wrong through homage.

We also have to assume that some of these similarities are actually coincidences. One gameplay section of Chapter 3 has you avoiding an enemy who only moves when you look at at it, a Red Light, Green Light mechanic from FNAF: Security Breach, itself a reference to a FNAF fan game The Joy of Creation. My understanding, though, is that the sequence originally had the enemy move in the dark and stand still in the light, an inversion of a sequence from Chapter 2 where the player character was only allowed to move when the lights went out while trying to escape an enemy. The earliest players of Chapter 3 found this too difficult, and because the “stop and go” mechanic was already finished, the developers made the smart decision to alter the sequence slightly to be more manageable than doing something drastic.

So if none of this matters, then why am I so distracted by these comparisons?

A Flawed Mystery

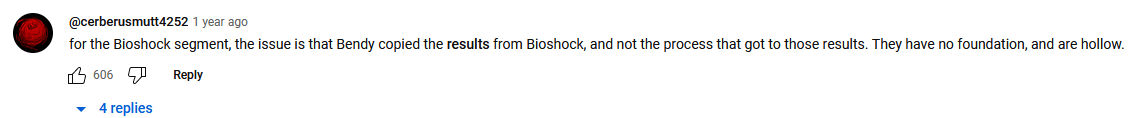

This indulgence in imitating other media – intentionally or otherwise – poses the same threat to Poppy Playtime that it did to Bendy and the Ink Machine. YouTuber Chris Portal highlights the many ways that Bendy lifts elements and scenes from Bioshock, “copying the results” (credit to YouTube commenter cerberusmutt4252 for this phrase) instead of merely taking inspiration. His personal experience also helps to show how the target audience of Bendy would have been too young to recognize similarities to the older game, which several comments on the video reinforce. Chris doesn’t do this to condemn the game for copying but rather to counter the developer’s claims that their title innovates through storytelling even if the gameplay is lackluster, yet it is noticeable to me how the poor writing in Bendy makes the end result feel closer to an incoherent ripoff than a game that simply wears its inspiration proudly. Bioshock takes so much from System Shock 2 that it copied part of the name and still feels like a complete and original experience. The developers were open even at the time about wanting to create a “spiritual successor” to System Shock rather than insisting upon themselves that they were incredibly original, thank you very much.

Poppy Playtime is no Bendy, thankfully. While Bendy feels like it was written piecemeal one episode at a time (reports on this are inconsistent, Chris Portal explains), Poppy Playtime does seem to have a well-defined story that simply isn’t shared enough with the player. This results in a lack of immersion, and I find myself thinking about other games I’m reminded of instead and hoping to guess the story through comparison.

Mascot horror primarily derives storytelling techniques from Five Nights at Freddy’s in the same way that many slasher movies draw inspiration for their villains from Halloween. When I type “FNAF” into my YouTube search bar, the first suggestions that come up are:

- FNAF lore

- FNAF lore explained

- FNAF timeline

- FNAF full story explained

- FNAF all lore explained in order

It’s not like there isn’t a lifetime’s worth of fan animations, songs, Let’s Plays, unboxing videos and so on for fans to search for instead; the series is just that oblique in its storytelling. The very first FNAF game isn’t even complicated, with the “twist” that several children were killed and stuffed into animatronic suits being (in the words of YouTuber GiBi’s Good Idea Bad Idea) closer to subtext. Questions like “Who is the security guard, and why do they keep coming back?” didn’t become part of the narrative until later installments. Only once FNAF became incredibly popular as a decoding exercise for fans to speculate about did derivative games follow suit with their storytelling.

Mystery games are the biggest exception to the idea that you can handwave away a lot of the explanation for video game worlds. While games such as The Last of Us put in the work to make their settings naturalistic, neither you nor I need a pseudo-scientific explanation for the silly elements in a Mario game. But a mystery needs a comprehensive design for the audience to feel catharsis. As the writer, you are asking your audience to piece together the answer to a central question even if you deliberately withhold key details in order to surprise them with a twist later. Outer Wilds starts you out in a universe that feels every bit as wacky as any Mario game only for it to slowly become clear that every fantastic thing you can stumble across is somehow connected in a grander mystery. Nobody asks you to solve it; you can leave the game at any time. But why would you? Cracking the secrets of these strange planets is thrilling.

In Poppy Playtime, you play as an ex-employee returning to investigate the sudden disappearance of hundreds of workers ten years prior, prompted by a bloody letter in the mail. The murderous toys are treated as a surprise to the player character, so it seems safe to assume the character’s ignorance of the orphanage or experiments. Yet most of the talking toys can tell that you worked in the factory at some point, which strikes me as odd given how many years have passed and how many people must have worked there in order for there to be “innocents” according to Poppy, the talking doll whom the franchise is named after. Starting in Chapter 2, Poppy spends a little bit of time helping the player with environmental puzzles before being captured by a giant talking toy named Mommy Long Legs (which is much less sexual in context, I assure you), who is later killed in an accident and her body taken by “the Prototype,” a godlike figure to the living toys. But even once Poppy is freed, she only offers a few cryptic lines about how you alone can save them all… before the train is derailed and the chapter ends.

August 31, 2024: With hindsight, I actually disagree with myself here. While it seems that Poppy herself doesn't recognize the Player Character, it's a bit of a leap to suggest that the Player Character knows no more about what's going on than you the player do. The events of Chapter 3 strike me as intentionally designed to make the audience question if the Player Character is truly ignorant after all. I still believe the series plays it's cards too close to its chest at times in a way that's more frustrating than intriguing, but this ambiguity specifically is not necessarily a bad writing decision.

In chapter 3, you find yourself in an illusory hallway sequence modeled after the Silent Hill “Playable Teaser” that briefly dominated the Internet in 2014, where the mandatory creepy radio implies that you either are the mysterious creepy founder of Playtime Co. or are otherwise closely connected to him. When you meet Poppy again immediately after, she saves you from being attacked by a metaphor for your guilty conscience to insist that you “didn’t do anything wrong” and are “only here to help.” Did the nightmare hallucination lie to you, or is this dramatic irony? The player character does not contradict Poppy, nor do they agree with her. They say nothing and ask no questions. I’m not convinced the player character has a voice at all.

Speaking of: chapter 3 also introduces the voice of Ollie over the radio, who helps us navigate the neighborhood orphanage. At several points, he will become a fount of exposition regarding new villain Catnap and his relationship with the Prototype. He does not explain who he is nor if he is a toy or a child nor what his own goal may be, though Poppy does vouch for him. As we near what feels like the end of the second act with a handful of voiced characters to pick from, nobody has taken it upon themselves to explain who or what the Prototype is, what really happened to the children in the orphanage, or why there are giant living toys roaming the factory-orphanage-laboratory. Like with FNAF 1, it’s not hard to read the subtext and conclude that there must be a connection between experimenting on children and living toys, but there are characters who would know for sure and will not explain.

It isn’t all bad, to be clear. We do learn, from Poppy herself, that the missing employees were killed during “the Hour of Joy,” wherein the toys killed every single employee in the factory and dragged their bodies underground. The missing-employees mystery is the one you the player are the least personally invested in, and giving a straight answer late enough that there are bigger questions to latch onto is good storytelling. It makes sense that we’re only learning this now, once we know enough about the setting and characters to understand the role of the Prototype in the Hour of Joy and why these toys may hold a grudge toward their captors. The audience is allowed a moment of catharsis that doesn’t spoil any later reveals.

But a mystery that can be answered by allies explaining what they know to each other is frustrating rather than compelling. Poppy and Ollie insist that they are trying to help the player character, and nothing is stopping them from sitting down to have a tea party and get on the same page except for the fact that doing so may spoil a later twist. The solution to this problem is not to leave players in the dark but to write characters who don’t know everything, or at least who pretend they don’t. It’s not hard to write a character that misleads the player while still appearing trustworthy – Bioshock does this, famously – but audiences need to believe that they understand what’s going on for a mystery to be compelling and a twist to be surprising.

If Poppy or Ollie do betray the player character in subsequent chapters, it won’t be much of a surprise because they’ve only been minimally helpful so far. It also won’t be a relief if they turn out to be genuine, because we’re not emotionally close to them. Poppy’s sudden personality shift come chapter 3 is worrying because it suggests that the writers aren’t entirely confident with their title character. Compare this to the sock puppet Ricky from My Friendly Neighborhood, who is helpful and honest with the player even as he begs you not to follow through with the main objective of the game. It is a genuine relief to find that he never had any intention of betraying you; he’s your friend, after all.

Inna Final Analysis

Mob Entertainment has made some genuinely bad decisions, but some criticisms of Poppy Playtime feel like jumping on a bandwagon to hate a game from a controversial genre. I’ve defended the series, but Chapter 3 gives me pause. The comparisons to other media would be nowhere near as distracting if the story felt better written this many years into the franchise; for the first time, the very distinct identity of Poppy Playtime is a little lost beneath the familiar imagery of other media.

This forces me to ask some uncomfortable questions. Is it possible the comparisons to other media aren’t inspiration but nostalgia bait to cover for a lack of originality? Could the developers have modeled Chapter 1’s release after Bendy because they thought it their best chance at getting a hit? Would they have made any of these writing decisions if other franchises hadn’t first? Multiple people have drawn comparisons between Ollie and the protagonist Gregory from FNAF: Security Breach, and there is speculation that Poppy Playtime is foreshadowing the same plot twist for Ollie that Gregory received in the Security Breach: Ruin DLC. It would be the most predictable and least satisfying direction, but it’s been done before successfully, so maybe it will happen here too.

I have gone out of my way to give Mob Entertainment as much of the benefit of a doubt as I possibly can, but is it any wonder this franchise rubs people the wrong way?

This article ended up being late because of technical issues. This means I lost what I feel was the golden window where not all the big-name Let’s Play YouTubers had finished Chapter 3 and it was still on everyone’s mind. Yet the extra time was useful because it gave me a chance to correct factual mistakes about the storytelling. Ironically, the people who I’m concerned about seeing this aren’t the ones who will take issue with me praising the series but rather the people who might throw out my entire argument if I get any details wrong simply because I “don’t get” the game. Those errors did weaken my argument, but they did not invalidate my opinion on the quality of the writing.

People say that there’s more lore to be found in the spin-off title Project Playtime. I already spent much longer than I’d ever intended to doing research for what is just an opinion piece, and in doing so I have grappled with my feelings and even changed my mind a few times, but the buck stops here. Storytelling media should not have homework; this isn’t an ARG, it is a $25 retail product. Nobody would be okay with paying full price for a cinema ticket only to be told halfway through that they needed to watch a fifteen minute short film to understand who half the characters even are. And it is by no means just a Poppy Playtime problem; every trans-media “indie series” has too much going on for anyone to follow. It’s no wonder that people feel the need to get their opinions from YouTube middle men like Game Theory. How are you supposed to have an informed opinion on these series unless someone else gets paid to do the research?

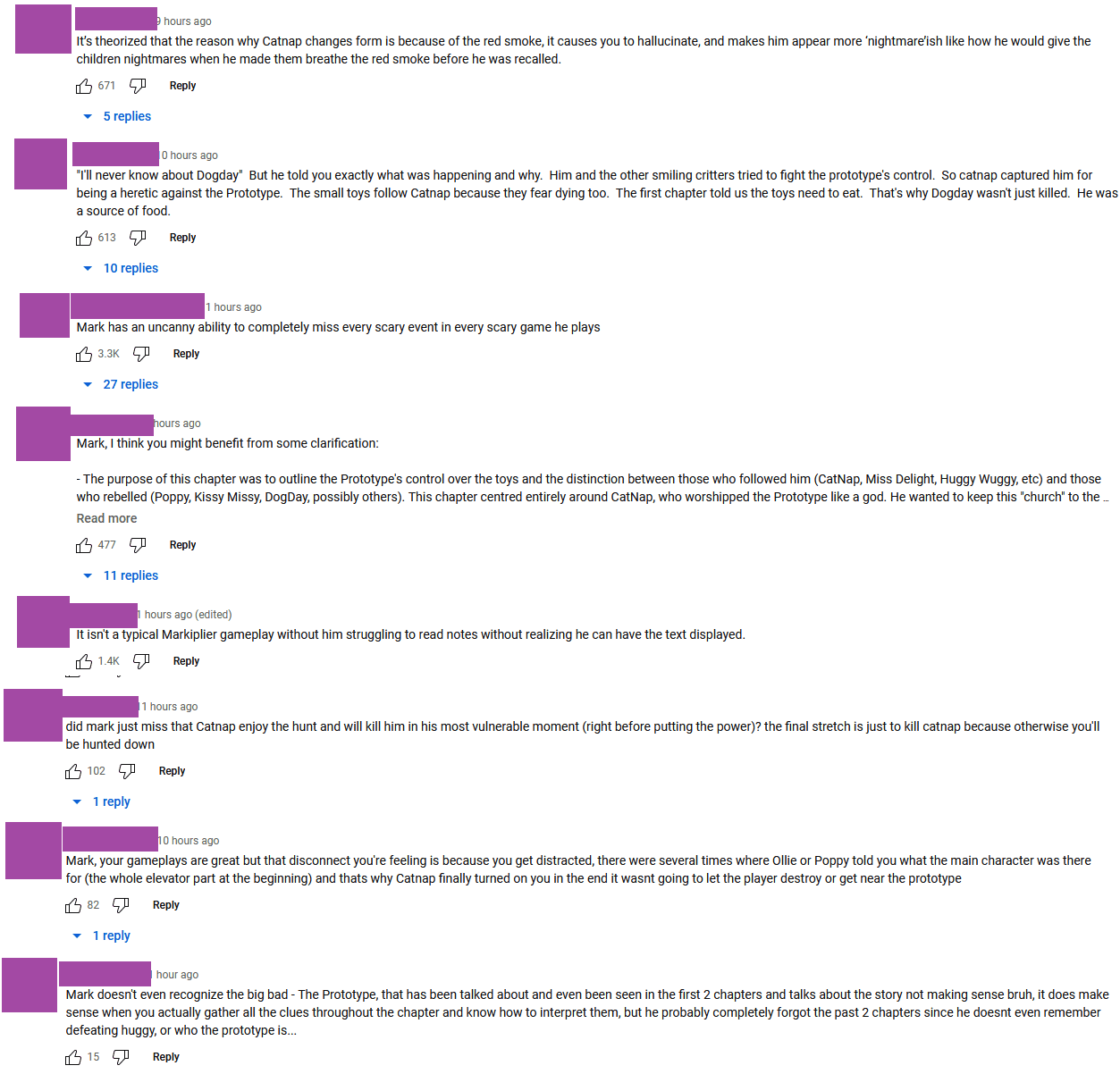

In his most recent Poppy Playtime video, YouTuber Markiplier echoes some of the feelings I have, that the developer isn’t able to give audiences enough information to be hooked on the story. Commenters insist that it’s his fault for missing details in the game world and not listening to character dialogue. But while Mark can be easily distracted and miss the occasional story beat from time to time, I’ve watched him play Bendy, FNAF, Amnesia, all of which arguably have much more obtuse storytelling, and he feels immersed and emotionally invested even when he doesn’t always understand what’s going on. Here, though: he’s baffled by the story, I’m distracted by comparisons to other media, people are frustrated with “padding.” The boss fight at the end of Chapter 3 is a huge sticking point for fans and is so mechanically bloated that I have to wonder if they’ve pushed the Grabber mechanic as far as it can realistically go.

Something about this game is not drawing people in the way earlier chapters did, and that’s upsetting to me as a fan.

Poppy Playtime has a lot of staying power. After sixteen months of quiet development, Chapter 3 was still able to get the Internet’s attention immediately. Moving forward, though, I think the game needs a change of direction to stay relevant. It’s unlikely that the IP will ever stop turning a profit completely; with enough overhead, you can advertise anything into becoming a sustainable franchise, and there’s little incentive for Mob Entertainment to take their cash cow off life support in favor of something untested. But as a piece of media, the game needs some tender loving care that it’s not getting right now. The escalation of development time, store price, and poorly-explained story beats is quickly going to start working harder against the game than it’s currently working in its favor. Chapter 3 was a success, but poppies are short-lived, and people have other games in their garden they want to show off too.

Poppy Playtime may cost several hours wages to play, but this article is entirely free! If you'd like to throw a bit of change my way to show support, you can donate as little as a dollar to my ko-fi. It all makes a difference.