- Published on

Morality Play, or: What Makes a Morality Mechanic, Anyway?

- Authors

- Name

- Katie Quill

Word Count: 5000

Reading Time: 40 Minutes

Any video game is a complex beast, but a story-driven one doubly so. Games like Mass Effect, Skyrim, or Deathloop aim to sell you the illusion of an entire world of responsive characters. Others, like Frostpunk, have almost none of the same design principles but still seek to model human behavior in a way that enhances the story. Though there are hard limits on what code can accomplish, art thrives at abstracting complex realities into shorthand; we don’t need an exact representation of reality, just a meaningful one.

Morality mechanics in video games are almost as old as the medium itself, but even among more well-known examples, we find a lot of variety in how games model decision-making, the outcomes of player choice, and how those tie into thematic statements. There is no formula, but there are recurring pitfalls, and exactly what constitutes a “morality mechanic” is open to interpretation. I’m using the term broadly, referring to explicit in-game mechanics players are expected to factor into their decision-making as well as games whose ending passes judgment on specific actions you-the-player have taken. There is a lot of overlap with “reputation systems,” but only mechanically, as I believe those serve a different function.

This is an exploratory piece examining several factors that go into modeling moral behavior in video games; in particular: Metrics, Rewards, and Thematic Incorporation. These are somewhat arbitrary—I don’t have special insight into how developers conceptualize their mechanics—but I think they’re helpful guideposts. I’ll also talk about edge cases, games that prompt and maybe even respond to moral questions but don’t have an explicit mechanic for players to engage with.

I talk about a lot of games for this article, but almost all of them are CRPGs, and many of them come from Bethesda, Bioware, or Obsidian Entertainment. There were even more I cut because I already had so much to say. Creating a comprehensive analysis of morality systems in video games would take months or years and result in a book rather than an article. Still, I’m happy to have had the opportunity to write about it.

Obviously, I’m not the first person to write about this; in fact, I was originally just going to talk about the thematic implications of Dishonored before realizing I had a lot to say. So I didn’t read any of the dozens upon dozens of other think pieces on this topic from the past few decades. If this covers familiar ground or lacks widely-accepted theories, forgive me; I’m more interested in exploring my own relationship with these games.

Fictional Metrics for Fictional Behavior

Some CRPGs track player decisions very granularly, recording as many actions as possible for its calculations. On the opposite end of the spectrum are games that respond to one major decision, usually to determine which Ending the player gets. More games fall closer to the latter, using several big moments where the player is expected to reflect on the weight of their actions and behave accordingly, but games that really commit to their moral mechanics will often strive to be as granular as the developers have time to implement.

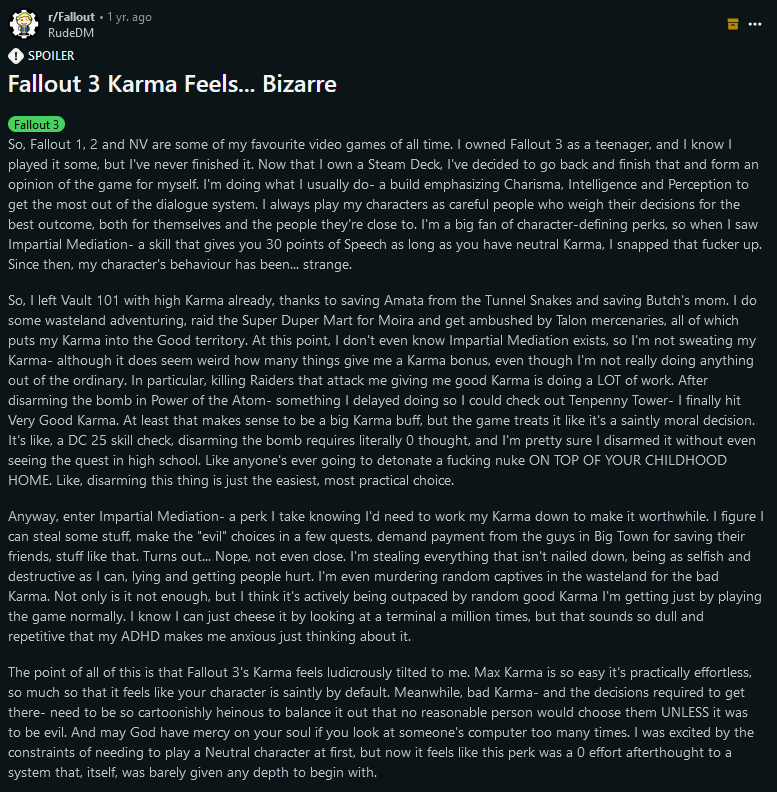

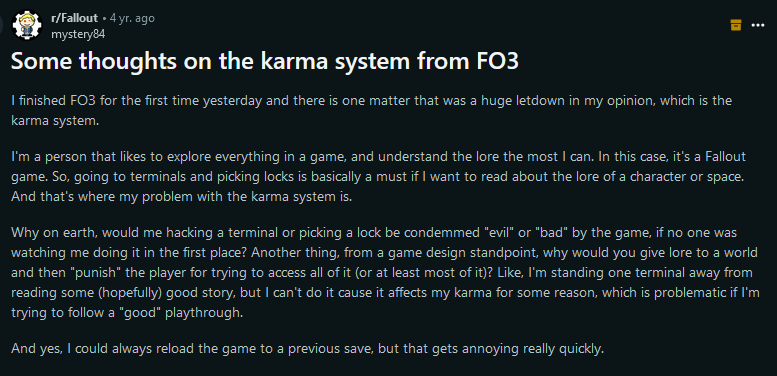

Press for Fallout 3 bragged about its Karma system, which scored the player-character from -1000 to 1000 with terms from “Very Evil” to “Very Good.” Not much room for interpretation. Giving away resources, helping noble people, and donating money raises Karma while killing non-evil characters, stealing, and giving drugs to addicted characters lowers Karma. Positive, neutral, and evil Karma levels all give players access to unique companions and resources, but Bethesda’s desire to “have it all” by equally rewarding playstyles did not sit well with Fallout fans; the simplicity of it all makes the system feel shoehorned in. Fallout: New Vegas is built on top of Fallout 3, so it retains the Karma system, but there it feels vestigial because of how heavily the game leans into the presence of factions and a much more engaging reputation system.

Developers’ relationship with “the Meter” is fascinating. Bioware’s Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic measures how aligned the player-character is with the Light Side or Dark Side of the Force. While every character has access to the same abilities, where the character falls along the meter heavily affects the cost of Light Side and Dark Side powers. It’s simple and elegant, but it lacks depth in a way that feels emotionally unsatisfying.

The developers seem to agree, because they took a different approach with Jade Empire by introducing two complementary philosophies the player may follow: the Way of the Open Palm and the Way of the Closed Fist. Each is presented as roughly equal to the other; a 2007 Gamespy review (page is unsecure; use discretion) describes it as the difference between helping everybody at the cost of potentially fostering codependence versus a “tough love” approach that desires to strengthen others through adversity. In the Western world, this risks coming across as false balance (or “both sidesing”), but it fits a lot of Eastern philosophy, particularly the concepts of Yin and Yang that seem to be the primary inspiration. The game then fumbles this notion by forcing the player to choose between two endings, each associated with one philosophy, and one portrayed as unambiguously Bad; you can guess which.

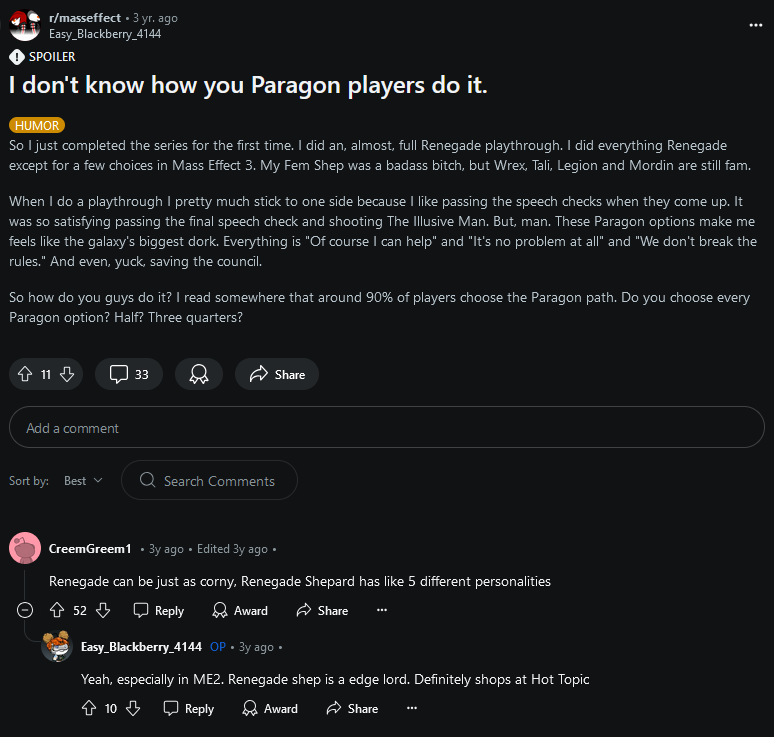

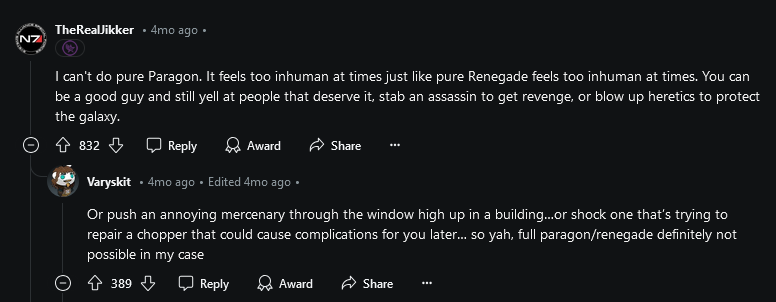

Attempts to further evolve Bioware’s mechanics in Mass Effect saw a return to Western values in the form of “Paragon” and “Renegade” options—two character archetypes rather than a moral dichotomy. Archetypal dialogue choices (and “interrupts” in the sequels) are plainly telegraphed in the UI in a way that cannot be misinterpreted, which is a step up from many games that expect the player to intuit how the writer will judge their actions. The most important innovation, for this section, is the fact that Bioware gave these archetypes separate meters, meaning they are no longer in direct competition; players may choose freely what to do. In fact, many people find that “fully committing” to one path over the other results in an unrealistically silly character.

In practice, though, most people gravitate heavily toward Paragon decisions. Despite being just a different kind of power fantasy, the unfavorable consequences of some Renegade actions and how the player-character is chastised for them still codes that playstyle as less optimal. And on a macro-level, the game pressures the player to commit hard to one path by locking some of the best dialogue options behind very high archetype scores. This actually punishes roleplay; a diplomat may still be aggressive, and a pragmatist may have moments of idealism, but the code does not care. Even though having two contradictory but complex approaches to problem solving is a logical extension of Bioware’s prior experimentation, design decisions that reward extreme commitment (and the way dialogue presents the Paragon route as absent any true flaws) undermines its effectiveness.

The dreaded Meter is dominant for a reason; it’s easy for a computer to add and subtract from a variable. Whether or not the results of your actions affect every detail moving forward or just the ending cinematic, it’s hard to imagine an elegant alternative. Bioware’s attempts to “fix” morality mechanics show how restrictive the simple meter feels for developers and players, and their inability to revolutionize the idea creates this looming dread that morality mechanics are fundamentally flawed.

Fortunately, as reputation systems show us, the Meter is useful for creating complex systems if you have enough of it.

Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar released in 1985 as possibly the first game to incorporate what we’d call a morality mechanic. As a 2020 New Yorker article explains, series creator Richard Garriott would receive fan-mail detailing how players approached the first three games, taking advantage of the open world and non-linear story in order to steal and kill as a quick road to power. Saddened that his games rewarded such brutal behavior, Garriott felt compelled to study a variety of ethics in preparation for his next project.

Most CRPGs with heavy morality systems still have some external threat that defines the main conflict. The goal of Ultima IV is instead to become the “Avatar” through embodying the eight virtues of honesty, compassion, valor, justice, sacrifice, honor, spirituality, and humility. Each has its own meter.

Ultima IV’s measurements are possibly as granular as a game can realistically pull off. Per a helpful wiki, allowing a non-evil enemy to flee or even fleeing from a non-evil enemy will raise Compassion while attacking non-evil creatures lowers both Compassion and Justice. The interconnected nature between the virtues push the player toward moral decisions in order to complete the main quest. By design, the game rejects the idea that you can be a bastard and still have a fulfilling experience.

It would be too much to ask every game to do this; the mechanical freedom that a real-time 3D open world offers makes tracking player behavior significantly more difficult than it was in 1985. But the popularity of reputation systems shows that there is a strong desire for games that respond to player actions beyond a thumbs up or thumbs down. Ultima IV shows that developers can be more specific, with virtues that have complex interdependencies, and Bioware’s experiments with Jade Empire and Mass Effect suggest that there are other dimensions to explore.

I am reminded of Magic: The Gathering, the collectible card game that uses colored mana as resources. In the lore of the game, each color represents unique priorities: Red values freedom and action, Blue technology and logic, Green instinct and preservation, etc. On their own or even combined into groups, these create the foundations of interesting moral philosophies. As games become increasingly complex, shouldn’t their understanding of different ways to measure morality do the same?

Optimizing for Moral Desserts

Beyond the Meter, some games will use a “soft” moral mechanic where players are presented with difficult choices that affect the game world moving forward. In many cases, players are also able to unlock a “compromise” which represents the best of both outcomes. This makes sense in the abstract—compromise is hard but yields better results than competition. Yet many emotionally invested players walk away dissatisfied. The challenge rarely feels appropriate to the reward: players aren’t expected to find common ground, just to pick optimum dialogue choices or do a bit more exploration to find a detail other characters missed. This design decision feels like a natural extension of older games that lock the “best” ending behind harder difficulty levels or optional challenges, a relic of a much older state of the industry.

One of the more famous recent blunders in this regard occurs in Bethesda’s Starfield. One mission has you discover that a generation ship has entered orbit around a planet they were promised upon leaving Earth. In the time between their launch and now, interstellar travel became so easy that the planet now belongs to a single corporation. The game doesn’t entertain the idea that the planet might belong to the people it was first promised to or that a vacation resort doesn’t need an entire planet to itself; instead, your options are to send the colonists to a new faraway planet or kill them all. But the game does offer you a “compromise.” You can simply have the colonists become indentured servants to the resort, who in turn save money by firing their staff. In a more cynical game, this would be a hilarious subversion of lazy compromises in CRPGs; in Bethesda’s hands, it feels like an example.

There are games that handle the question of moral desserts much better. Frostpunk asks you, as captain, to make sure the city survives by any means necessary: child labor, sawdust in the food, prisons or public flagellation. The strategies for harder difficulties push the player into apathetic, totalitarian policies that solve nothing but keep people obedient. Because it’s just a video game, this is fine, but engaging with the fiction and its themes leaves a player drained afterward from the weight of their decisions. Instead of rewarding idealism, the game demands moral compromise to survive at all.

A good moral choice in fiction requires deciding between the lesser of two evils or two incompatible goods; it should be uncomfortable for some people and easy for others. Mass Effect 2 accomplishes this with the optional Zaeed loyalty mission, which forces the player to choose between earning Zaeed’s trust—and making him useful for the final mission—or preventing him from committing a horrible atrocity. Some people won’t have to think about it, but others will, and it feels like a meaningful choice in a game that otherwise spends a lot of time holding the player by the hand; the Arrival DLC doesn’t even let you choose not to slaughter an entire star system.

More often than not, role playing games seem to clearly telegraph which decision they consider to be the correct one, rewarding you handsomely for following the path. Mass Effect 3 ranks its endings based on how difficult they are to get, but also in ascending order from Renegade, Neutral, and Paragon. Just like with Jade Empire, the system fails to live up to the idea that these are contrasting but equal worldviews.

The problem may lie with the fact that the goal of many a developer is to make a game that is only fun and rewarding to play. Even FromSoftware, despite what diehard fans may say from their high horses, makes games that push you toward success. YouTuber SuperEyepatchWolf suggests in his video on Fear and Hunger that a game only becomes cruel toward the player when it is both challenging to complete and punishes you heavily for failure. What does morality look like in such a game?

Pathologic is a 2005 RPG originally developed by Ice Pick Lodge that perfectly captures the warmth and comfort of a shallow grave. You-the-player take on the role of one of three doctors—an academic, a surgeon, or a miracle healer—to save a small Russian town from a supernatural plague. Following its theme of Russian Optimism, the game forces players to confront normal thoughts such as “Do dying people really need all this food for themselves?”, “Well, I am being paid to attack this child,” and “He’s already dead; he doesn’t need all his organs.” Though the game does have something of a reputation system, the real strength of its design philosophy comes from its decision to withhold rewards for upstanding behavior.

Taking it a step further, though, the game doesn’t reward cutthroat pragmatism with mechanical boons but rather physical items. This isn’t super meaningful in isolation, but every item a player can carry in Pathologic is something that exists in a broader economy and doesn’t disrupt existing resource management. You are never gifted a powerful gun the game can’t take away from you or a +20% healing bonus for your character. Everything gained for giving into temptation only matters as far as you can exploit it, placing even more power in the hands of the player to make further decisions… and justifications.

It is possible in Pathologic to get a compromise ending that evokes the best of its two competing worldviews. While some games are disappointing in this regard, rewarding players for extra work isn’t bad per se. Pathologic succeeds in proposing a balance between two seemingly incompatible worldviews in a way that Jade Empire failed, but only by forcing the player character to actually establish the in-universe common ground that feels rewarding. And critically, the two competing philosophies in question don’t feel incomplete on their own in an attempt to pressure the player into doing extra work.

Thematic Shortfalls

Some years ago, the buzzword-of-the-day for Internet people to fight over was “ludonarrative dissonance,” a term loved by critics and hated by fandoms. It described the feeling of playing a game that fell short of its thematic intentions through gameplay that is mismatched to the story. For example: games about “war is bad” still often try to make warfare fun to play through, and this comes across as disingenuous to some people even though others don’t mind it.

Bioshock and Bioshock 2 are much more similar than differing opinions on them suggest. Both have you traversing the decaying underwater city of Rapture, killing every addicted and mentally ill person in your way as you debate the philosophy of self-actualization with rich losers; parts of this franchise have not aged well. They are violent games by nature of being first-person shooters, and each game has a Good and Bad ending based on your behavior. Both also come close to having very solid moral themes that fall short because of a few key decisions.

In Bioshock, you are judged based on how you treat the small children who have been turned into vessels for a drug that grants superpowers. By curing them, you are given the Good ending; by killing and harvesting them for extra power, you get the Bad ending; simple, easy to pitch in a boardroom. What makes Bioshock interesting as a specimen is that it doesn’t judge you for killing people (even rich ones), just whether or not you exploit or save the vulnerable innocents taken advantage of by greedy elites. Setting aside the elephant in the room for a second, Bioshock is easily read as a scathing critique of our own participation in social ills. We benefit from the fruits of sweatshop and slave labor because these feel too big to dismantle, even when they’re as small as “crunch time” for video game developers. We choose not to take a stand against government agencies or corporate interests, at least not on the level that forces societal change, and instead live in their world but shake our fists impotently. The children in Bioshock deserve mercy, but if the Splicers are us, they’ve made their bed. In that light, the game is cynical—portraying the average person as willfully stupid, destructively self-interested, and compliant with blatant evil—but it is a far more cutting criticism of the moral fiber of the “developed world” today than in 2007.

The insurmountable flaw in this reading is that Splicers are not apathetic participants but victims themselves. The game’s depiction of mental illness and addiction was behind the curve even for the time. We can imagine a version of the game that excises this problem, but we cannot play that version.

Bioshock 2 takes a step backward with its morality mechanic. In the first game, the only adult spared your wrath is Doctor Brigid Tenenbaum, a character who is by no means innocent but is actively working toward a redemption that every other citizen of Rapture has given up on. While Bioshock 2 still judges you on your treatment of the infected children, it also has you decide to kill or spare three specific characters who are considered more narratively important than your common Splicer and thus uniquely worthy of life. The game dresses this up by framing these three as important specifically to the character of Eleanor, whom you are trying to save, and that she is “learning” whether to forgive or hurt people based on your actions. But Eleanor must already have a massive disregard for human life for your treatment of the Splicers not to affect her at all. While there is certainly a difference between killing in self defense and killing somebody who is entirely at your mercy, the ability to spare people would hold more weight if, like in Ultima IV, the game considered regular enemies as people too.

Bioshock 2 is especially disappointing in this regard because the decision to kill these characters actually is an emotionally challenging one. Take the character of Gil Alexander, who underwent a monstrous transformation as a result of a scientific accident. He records a voice log in his last moments of lucidity asking that, should anyone find him, they euthanize him. The transformed version of Gil that you meet, “Alex the Great,” pleads for his life once you finally have him at your mercy. So whose wishes do you respect?

Bioshock 2 would almost certainly be more fondly remembered if it had stuck with the same moral mechanic as the first game. Each of the “important” characters is interesting enough to make you question if killing them is okay or not; none of them are any more innocent than Tenenbaum. By deciding for you that these people alone deserve to be spared, the game comes across as condescending in a way that the first doesn’t.

Heavily reminiscent of Bioshock, but much more cynical, is a game that doesn’t seem to be doing anything special with its morality mechanic on the surface. In Dishonored, you play as Corvo, a disgraced bodyguard framed for the death of the queen in a world set upon by a terrible plague. Through multiple open-world levels, you stealth your way to each of the true conspirators and dispose of them as you wish in your quest to save the young princess and clear your name. The game keeps an ongoing score of how you complete levels: “low chaos” if you rarely get seen and rarely kill people, “high chaos” if you act like a wanton mass murderer. Each unlocks the Good and Bad ending, respectively.

Like Bioshock 2, Dishonored has some accidentally interesting moral dilemmas. You are given non-lethal options to deal with the conspirators, and while killing them doesn’t automatically place you in a high chaos state, you gain a lot of points for doing so. The game incentivizes you to execute more complex plans in order to get the ending where you’re regarded as a noble hero. Except that many of these alternative fates are arguably much worse than a swift death. The twins are sent to their own slave mines, the head of the Inquisition is excommunicated and left to die of the plague in the streets, and you can even help a stalker abduct a woman before fleeing the city. Each of these may feel like an accomplishment, but they do not feel good. Yet you can do all of them and be praised by the game, which talks about how your actions taught Princess Emily to be a wise and just ruler. Oh hey, that’s what Bioshock 2 did! Although here, how you handle the “normals” does actually factor into your final score.

If you doubt that these weren't intended to be as horrible as they are, spend some time researching the retcons to Lady Boyle's fate if you help the stalker abduct her; the writers had regrets.

So why does it work for me in Dishonored? Mostly the tone. Bioshock 2 is trying to be a somewhat heartwarming story set in a bleak world about the importance of a loving family, speechifying to that effect. Dishonored tells a bleak story about bad people masquerading as loving family; it’s hard to read the thematic message of the game as anything but “better to be seen as a good person by others than to actually abstain from violence—hidden cruelty is more utilitarian than unsightly pragmatism.” Dexter, the 2006 television series, grapples with a similar moral dilemma to great effect, and I wish the writers of Dishonored had, six years later, recognized and leaned into that similarity.

What if We Don't, Though?

At the end of the day, there is nobody keeping score of our actions. Moral behavior in the real world is hard to pin down beyond the broadest strokes, subject to cultural influences and personal bias, to say nothing of the impact of religious beliefs. But games don’t need to pat the player on the back to explore ideas.

Soma asks questions about the nature of humanity by giving you-the-player multiple opportunities to kill or spare characters that range from pure machine to flesh-and-blood human. Your companion behaves as an inverse Jiminy Cricket, encouraging you to be apathetic; after all, the world is ending, and is eternal life on a dead planet, teetering on the edge of madness forever, really worse than nothingness? Though the game is about ethical decision-making, your actions never affect the direction or difficulty of the story, unlike Dishonored. A lack of feedback reinforces the weight of these questions because there is no reward for answering.

Prey (2017) might not feel like it belongs in this section, but bear with me. As an immersive sim built entirely from Trolley Problems, the game tries hard to respond to your decisions in a naturalistic way; characters pressure you to be a good person according to their values. It doesn’t feel like the game is scoring you at all, though it is possible to be so callous and sadistic that it gives you a Bad ending. What separates it from examples that simply hide judgment until the end is that, just before giving you the Good ending, the game presents one last choice—accept the friendship of your judges or kill them all. Even at the very end, Prey prioritizes agency, giving you-the-player a chance to pass judgment on everyone else instead. This is a miniscule change in comparison to what Bioware has experimented with, but it feels much more radical.

While Deathloop engages with some interesting philosophical questions, it doesn’t emphasize them as much as some games. Ultimately, the game is thematically a rejection of shallow escapism in the face of a difficult reality, with your goal to break the time loop and free everyone to face an unknown future together complicated by the fact that these assholes want you dead for threatening their debauchery. What makes the game stick with me, personally, is that when I found myself standing on the roof of a building with a high-powered rifle in my hands, unloading bullets into a crowd of people, the fact that they were mere computer programs firing back at me—and even in the context of the fiction, wouldn’t stay dead for long—did not stop me from feeling a little uncomfortable with what I was doing. It was unsightly pragmatism on my part.

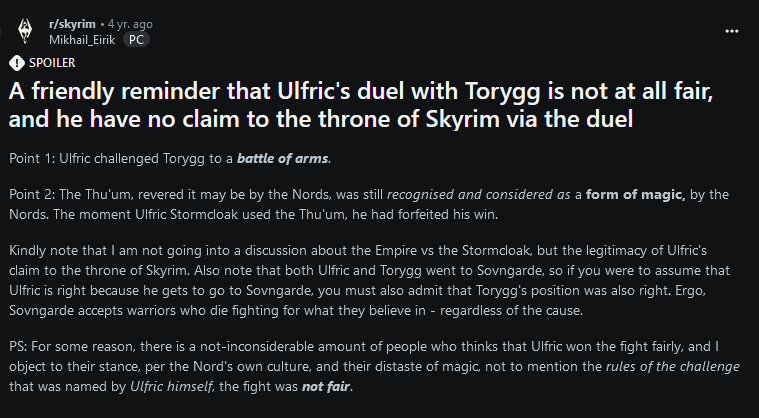

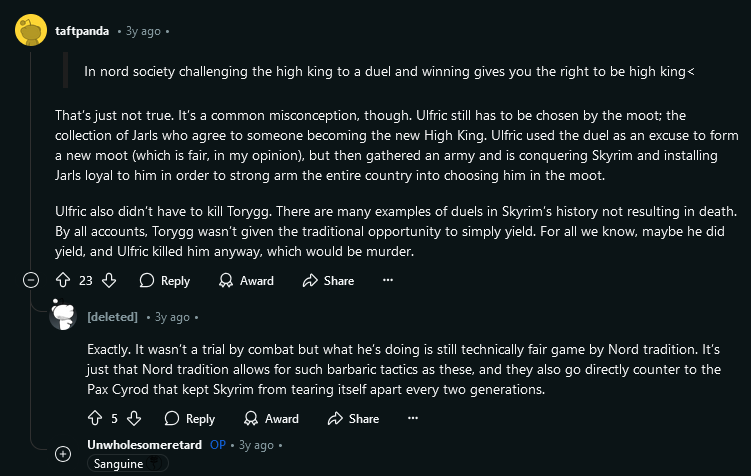

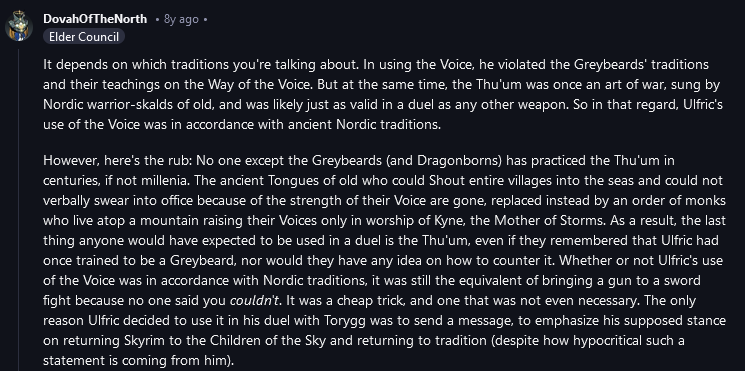

Skyrim is as much a meme as a game, but it has inspired some genuinely interesting anthropological discussions. To this day, fans debate whether Ulfric killing the High King was a crime or not within the bounds of their duel. This could be settled by someone at Bethesda creating a “canon answer,” but the fact that people will dig up real and fictional sources to use as references for their arguments is far more interesting to me than a clear-cut explanation.

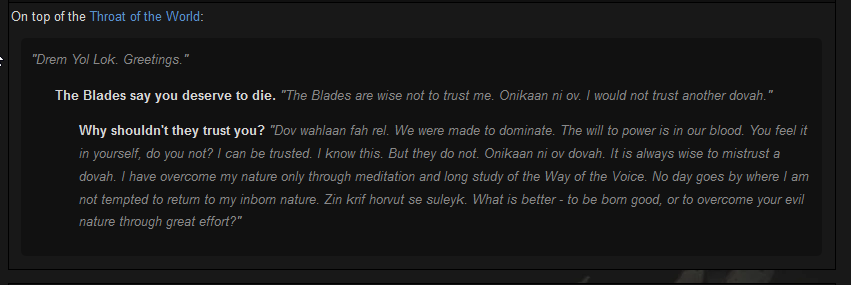

But there is also a particularly famous Skyrim quest worth mentioning. The player learns that the Graybeards—monks who have been teaching them how to save the world—regard the dragon Paarthurnax as their teacher. All dragons in Skyrim are ontologically evil (a thing people generally dislike in fiction), and the Blades, a dragon-hunting organization whom the player can actually summon into fights with dragons, will stop assisting you after learning about Paarthurnax unless you kill him. You can tell him this, and for many a young gamer, new to role playing games, this was the first time they were confronted with the question: “What is better - to be born good, or to overcome your evil nature through great effort?”

Skyrim does not allow players to abandon quests, and this is not one that the game allows you to complete in any other way. If you do not kill Paarthurnax, the quest will remain in your journal, incomplete, forever. This is a rare case where players prefer that to the alternative.

Inna Final Analysis

It’s easy to dismiss morality mechanics as the game (or more pointedly, the developers) wanting to be arbiters of right and wrong. Labeling actions as Good or Bad prevents games from responding to player actions in a satisfying way. In fact, many of the games on this list would be improved by eliminating judgment values entirely. What people like the least about Frostpunk is that the ending card tells you, the player, if you have crossed a line or not. How presumptuous.

Making a game feel truly responsive is harder than most developers even have time to implement, but we’ve seen examples of how they can augment the moral storytelling of a game even though it is never necessary. You may not agree with how Ultima IV defines morality, but you can enjoy managing it as a mechanical system much more than Karma in Fallout 3, if that’s the kind of game you’re looking for. And games that challenge our assumption that kind people will be rewarded, or that the best decision must be the moral one, often stay with players longer than games that make them feel good.

There is, again, no formula. Developers can go a lot further by considering the themes of their stories and which (if any) mechanics actually make sense to implement given the scope, scale, and timeline of development. For Prey, one thing was enough to make the point stick with players; for Pathologic, it was a pervasive design philosophy.

Do it wrong, and you’re a laughingstock. It’s surprisingly common to find games that profess to handle complex moral topics but fail as a result of developers simply not understanding the implications of their own story. Yet this sometimes becomes the ground for much more interesting thematic interpretations than the creators intended, such as with Dishonored. The result is art with interesting moral questions well beyond what the developers could deliberately invoke.

Thanks for reading.

2024 was rough, and 2025 promises to be no different. This article was a little differnet, and I hope to return to talking about specific media again soon. If you would like to help show me support, you can drop as little as $1 to my Ko-fi or find some of my fiction for sale on my itch page. If you have thoughts about what I've said here, please do reach out to me on Bluesky to share them! I'd love to know!