- Published on

Ugly on the Inside, Part 2: The Dark Rival’s Obsession with Second Chances

- Authors

- Name

- Katie Quill

In part 1 of this essay, we explored Bendy and the Ink Machine and how it used character appearances to signify a person’s good or evil nature. Here, we’re going to look at its direct sequel, behind the scenes information, and what we can possibly take from this whole affair.

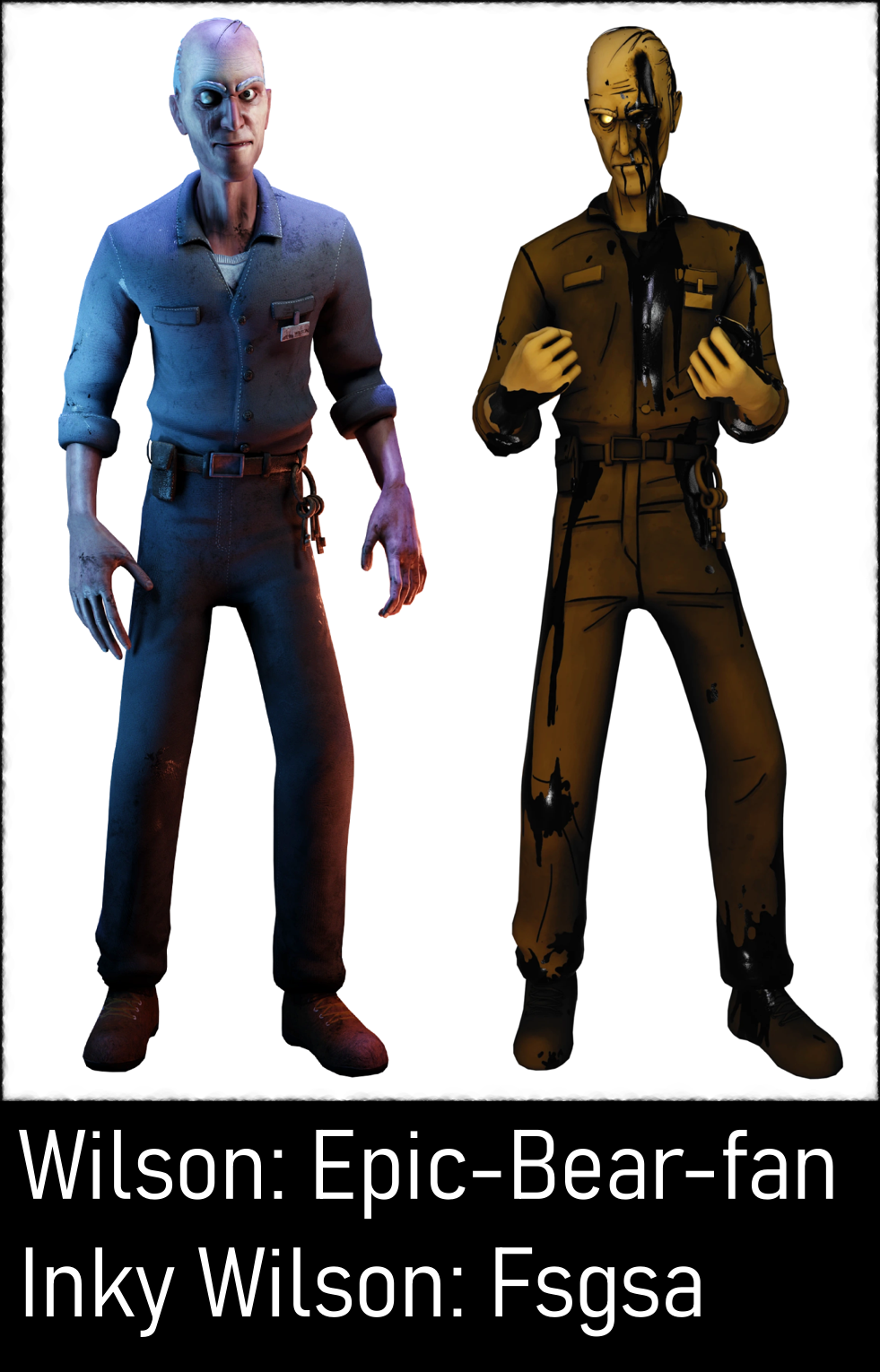

Wilson

“Now whether it was built for revenge or regret, I don’t know.”

My initial impression of Wilson, the first character Audrey meets in The Dark Revival, is that he’s so suspicious it loops all the way around to him being the most trustworthy individual you will ever meet. He’s the main villain. I suppose Kindly Beast thought they were being clever by having someone coded as insidious not be a red herring, but subverting a subversion is just playing a tired trope straight.

Joe suggests that they were trying to evoke “predator vibes” in order to make the audience uncomfortable with the character, especially since the protagonist of The Dark Revival is a young woman, but I don’t think that holds up. Creepy people in real life usually make us uncomfortable for a good reason, but Wilson doesn’t act like a predator or serial killer or even just someone who suspiciously always takes the same route home as you. If we’re supposed to interpret him as threatening, then it’s odd that Audrey doesn’t feel unsafe around him when they interact. It's more likely the goal was to have him fit the archetype of the mustache-twirling villain from early cartoons; they come close to pulling it off, but Audrey’s lack of reaction to how over-the-top Wilson is undersells that imagery.

His villain status is established as soon as Audrey enters the ink world and is never meaningfully challenged through the game. On the one hand, I can appreciate media that establishes an antagonist and sticks to it instead of demanding you be surprised by a predictable twist. But while I have a soft spot for self-aware villains (Count Olaf, again), Wilson isn’t present enough in the story for him to feel fully fleshed out. Joey Drew was a looming presence in BATIM, but we meet Wilson before he starts trying to fill the same role, and it works against the character.

Wilson is the only character in The Dark Revival to be 1) an old man who is 2) blind in one eye with a 3) raspy voice. Even the memory of Joey Drew who appears as a specter in the game is young and handsome rather than the old man we met before. It didn’t even occur to me at first that Wilson was also 4) balding because that’s such a normal thing in the real world, but he is the only human-looking character in the game not to have a full head of hair either. Once again, a primary villain is uniquely “less attractive” than the heroes.

“I can’t imagine anything about Wilson as anything but a joke,” Amber told me. “I know he couldn’t possibly [have] been intentionally made as anything but the most unsubtly evil person you could imagine…but it’s so insanely on the nose and heavy-handed that I can’t understand the intent…” She went on to say she found it upsetting that the game uses “factors like age, scars, or lost eyes as signs of evil or untrustworthiness.” Jack, who has less experience with the series, was simply baffled. “I’d go so far as to even say that this feels like I’m being pranked.”

The protagonist of The Dark Revival is an interesting case. We see Audrey in third person at the beginning of the game to establish her normal appearance, and when we see her in the ink world, she is something of a cross between the toon characters and the Lost Ones: dripping in ink but still conventionally attractive. At the same time, the fact that she is transformed by the ink this time is played as the visceral, sympathetic body horror that I described earlier. This is a huge step up from how the first game portrayed Susie, but despite Audrey having as much a voice and personality as Hendry does, we only get the briefest of glimpses of her emotional reaction before it's forgotten by the narrative.

While the way Audrey and Wilson are designed ties into our theme of conventional attractiveness as an indicator of goodness, the two are otherwise very good foils for each other. Audrey comes to discover that the father she doesn’t remember is actually Joey Drew himself, the memory of whom encourages her to save the ink world. Wilson also lives in the shadow of his much more successful father, Nathan Arch, the man who purchased the in-universe rights to Bendy after Joey Drew passed away. Whereas Audrey is respectful toward her father and his creations, wanting to see them endure, Wilson resents his father and seeks acclaim for himself.

Wilson’s control over the ink world is rooted in the lie that he killed the Ink Demon. Consistent throughout the game is his sentiment that the denizens of the world owe him for the deed, and anyone who disrupts his status quo is threatened with physical punishment or imprisonment. In truth, the Ink Demon is merely restrained (sometimes) to the toon form of Bendy whom Audrey forms a caring relationship with. While Wilson sought to kill or subdue the Ink Demon, the game ends with Audrey bonding with Bendy to save the ink world and start the cycle anew. The “rightful heir” of Joey Drew has taken control of Bendy. The final cutscene suggests that she has managed to do what Henry and Joey could not: redeem the Ink Demon and give it new life as Toon Bendy, the perfect version of itself.

In fact, the whole game really loves to hammer home the idea of redemption. Why might that be?

Kindly Beast

“Just do whatever it is you do and trust your leader… which is me.”

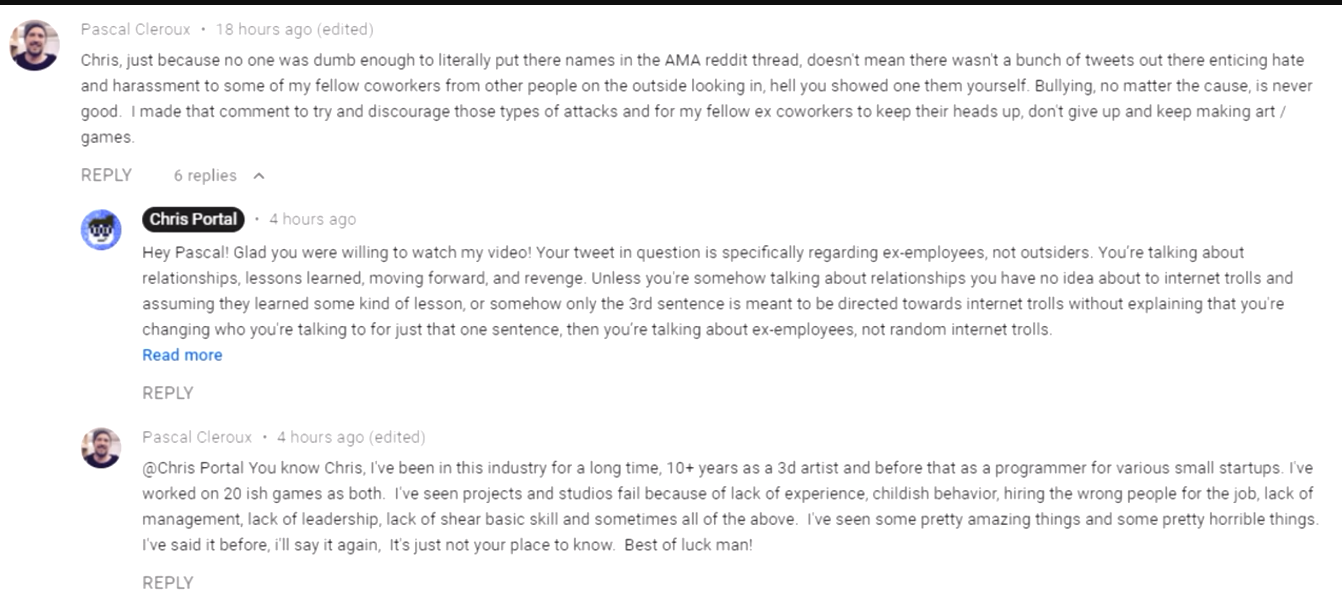

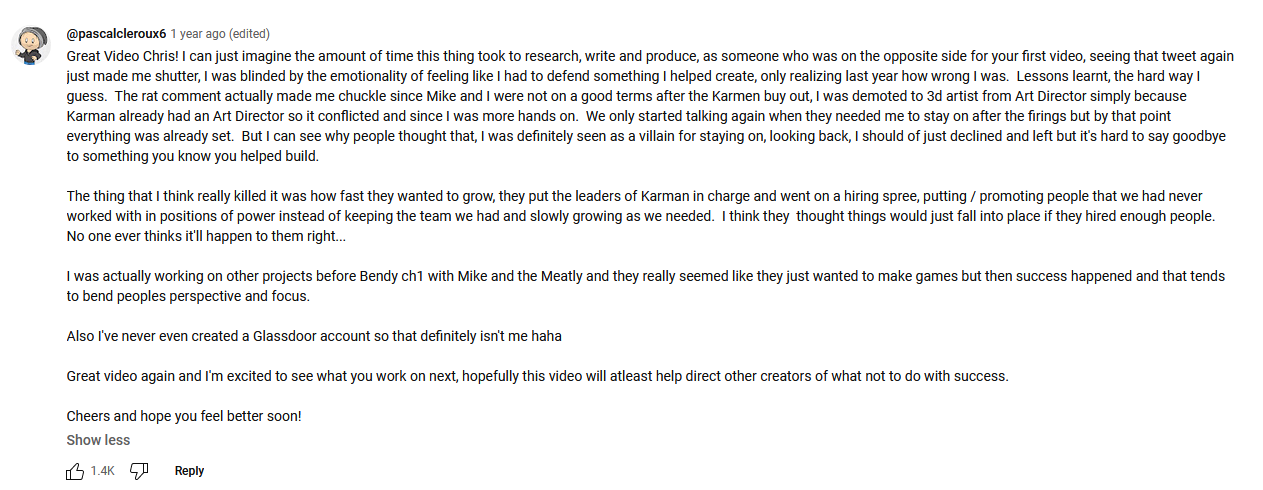

Almost everything I know about Kindly Beast (currently going under the name “Joey Drew Studios”) comes from two videos by YouTuber Chris Portal: The Bendy Controversy, Explained and The Bendy Controversy, Revisited. It’s bad form to take one person’s word on everything, but they’ve been well-received by former employees as a fair representation of the allegations and factual evidence. I also have no intention of simply regurgitating his own points for 2000 words, so let’s just start with a spew of random details and move on quickly.

Allegations of mismanagement, lies, verbal abuse, and threats from members of the board

CEO Mike Mood hired Cynthia Desjardins, his sister, to be the sole HR employee despite being warned it was a conflict of interest

Members of the board throwing out work done by employees for the game Showdown Bandit in order to release a version made by themselves that was a critical and commercial flop

Company did not acknowledge bugs in the final chapter of BATIM for 6 months and made excuses for why they were never fixed

Promoting an office culture of “get it done, good enough”; finishing products swiftly was a higher priority than optimization and polish

Poor enforcement of policy regarding fan-made content; contest winners were treated inconsistently; fan-made maps and renders were used in official content without permission

PR Manage was known for combative behavior online despite being the goddamn Public Relations Manager

Many of these aren’t particularly noteworthy for a big company, but as Chris himself notes: something being normal in the business world does not make it acceptable. The thing that sticks with most people, though, is Kindly Beast firing about 50 employees just before the winter holiday season without notice in 2019. Severance was promised along with assistance from a job placement agency only if employees signed a release form that would prevent them from bringing any lawsuits against Kindly Beast. It’s unclear if the company staggered terminations carefully to minimize the severance they were required to pay by law. A second round of terminations, months later, cut people who had been with the company since the beginning, people who had passionately defended Kindly Beast during the backlash to the first mass termination.

Cynthia Desjardins was promoted to Chief Operations Officer in January 2021, though it’s unclear where or if she’s employed at this time. She still publicly supports the Bendy brand on Twitter.

This is what people find damnable about Kindly Beast. Mike Mood, as CEO, gets a lot of well-deserved finger-pointing for the company’s behavior, but it’s important to remember that he’s only the most visible of Kindly Beast’s leadership. While I can admire that TheMeatly is PR savvy enough not to comment on the series except to thank people for praising it, his total silence on the controversy only means that he’s not a lightning rod the way Mike Mood is, not that he’s innocent. I think the difference between how they handle their own relationship with the public can best be illustrated in how they describe writing Bendy: TheMeatly insists—insists—that they knew everything about the story ahead of time; Mike Mood admits that the story was put together piecemeal in real time based on what they thought the audience wanted to see (with the exception of the ending). It doesn’t really matter who’s telling the truth here. The thing to note is how TheMeatly is careful not to say or do anything unflattering.

They say write what you know.

Amber and Jack were well-aware of this when I interviewed them. “When the allegations came out, I completely wrote off Joey Drew Studios,” Jack told me. “I left my Bendy fan discords, unfollowed artists on social media en masse…The only reason I agreed to even talk about it to someone was [because I have] a lot of opinions on it thanks to having had that experience.”

There were other people on the board of directors, but while their actions matter, they aren’t important to the narrative of Kindly Beast. Hopefully, they’re grateful that their status as less-public figures lets them slip away from public shaming like the oily weasels they are. Consequences for them will most likely remain restricted to how their peers in the industry choose to hold them accountable. This doesn’t make Mike Mood or TheMeatly somehow exceptionally bad or deserving of any kind of harassment, just the most interesting characters in this whole debacle. While they can’t be so good at micromanaging that they deserve blame for everything wrong with the games, their big personalities take up a lot of space in the room, and they are happy to take praise for the finished product.

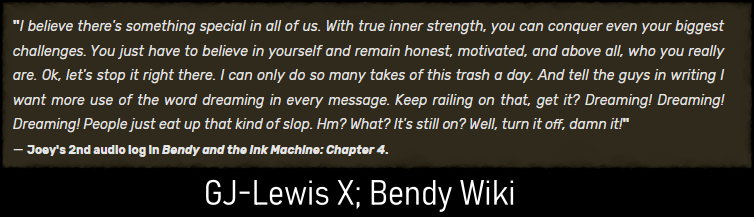

I’m not the first person to notice or point out that Kindly Beast changed its name to Joey Drew Studios seemingly to get a fresh start ahead of the release of Bendy and the Dark Revival. Joe pointed out that it’s a tactic often used by companies trying to save face. I also wouldn’t be the first to suggest that the company itself followed the story of Joey Drew as laid out in the game: an ambitious creator abuses his employees and ruins his legacy. What I have not seen anyone talk about, though, is how the sequel changes the character of Joey Drew. Now that they’re using his name for their studio, Kindly Beast really wants you to know that Joey Drew was a good person all along.

Joey Drew

"The only important question is: Who are we, Henry?”

Joey Drew is introduced in BATIM as the founder of the studio and owner (but not creator) of the Bendy characters. Audio logs from other characters in the first chapter describe him as obsessed with appeasing undefined “gods” with a ritual that has Satanic overtones. Another from Chapter 5 has Joey directly telling the inventors of the ink machine that “if you claim your failures are because these things are soulless, then damn it, we’ll get them a soul. After all, I own thousands of ‘em.” He displays an undeserved sense of ownership not only of the fictional characters but but also the people who work for him, describing them as “backroom incompetents,” betraying and sacrificing them to the ink machine, and luring Henry to the old workshop in order to clean up the whole mess for him. The only time we see Joey in person, he is a sad old man lamenting his “crooked empire.”

Following the final boss fight, there is either a flashback or start of a new cycle that ends with the real life Joey Drew inviting Henry through a door to restart the events of the game. It’s much more symbolic than literal, maybe to force content creators and fans to speculate about what the ending could mean in place of real catharsis. If we look at the ending through a symbolic lens, though, it simply reinforces the subtext woven through the game rather than casting it into doubt. Everyone is trapped in the ink world, forced to endure the cycle forever, and it’s all Joey’s fault.

However, because the game makes it deliberately unclear how real the events of the story are, The Dark Revival is able to revise history all it wants. The memory of Joey Drew tells us that nobody was sacrificed to the ink machine! They were all new fictional versions of real people. Beloved Joey Drew isn’t a murderer after all!

This was a horror game, right?

Bendy and the Dark Revival opens with the reveal that Joey Drew has been dead for two years and a new company, Archgate Studios, has taken over the intellectual property. This is a fascinating idea that adds a level of realism we don’t see a lot in Bendy’s contemporaries. William Afton has been the primary villain of Five Nights at Freddy’s for something like 30+ years in-universe, which stretches suspension of disbelief as the series gets further from its true crime roots and deeper into science fiction. For Bendy, though, this means that the ink world and its problems are no longer as closely tied to Joey Drew as they used to be.

Just before discovering an in-game tombstone honoring Joey Drew, Audrey encounters the much younger “memory” of him. What in any other story would be a fascinating deconstruction of the historical revisionism inherent in the notion that we shouldn’t speak ill of the dead becomes distasteful in the hands of Kindly Beast. Joey admits that he was a flawed and bitter man in life who came to regret his decisions, but Audrey experiences no conflicted feelings or misgivings like I would if I I discovered my long-lost secret father had been abusing his employees. Her unquestioning acceptance of his version of events, where Joey is easy to forgive and remembered fondly, is how the creators want the audience to feel.

Amber discussed how the depiction of Joey Drew in The Dark Revival affected her. “[The allegations] massively made me against the game around the time the last chapter came out…and [it] became all the more disgusting when the second game came out and tried its best to redeem and recharacterize Joey Drew as a more sympathetic character.” For her, this interpretation of Joey Drew is immensely disrespectful to the real-life game developers who regularly experience abusive working conditions without much hope of seeing justice.

I hardly need to remind you that the new, more likable version of Joey Drew is much more conventionally attractive than the villainous version we met before.

Joey’s sentiment that neither the past nor present define a person suggests a redemption arc that we don’t see him or anyone else go through. Audrey has nothing to be redeemed of, Wilson never regrets hurting people, Susie has learned nothing from her experiences in the previous cycles. The game isn’t about redemption, it’s about how “someone out there is messing with what’s in here.” But this suggestion that the ink world was fine before Wilson arrived is wrong; Joey Drew brought the world to life and is responsible for the suffering of its residents, not to mention the Ink Demon itself. For all his talk about personal growth, about once blaming everyone but himself for his mistakes, Joey still refuses to acknowledge that the people trapped there are suffering because of him, forever, until Audrey fulfills the role of savior that Joey had initially thrust onto Henry.

“I want Mike Mood and TheMeatly to give a proper apology,” Jack told me. “I want them to go the fuck back and release the version of Showdown Bandit that the passionate folks of Kindly Beast worked on. I want them to start actually thinking about games as art instead of products.”

“But that will never happen.”

How to Enjoy a Guilty Pleasure

“A lump of clay can turn to meaning if you strangle it with enough enthusiasm!”

One of my favorite writers is H.P. Lovecraft, a man famous even in his own time for being regressive and bigoted compared to his peers. This infects all of his work to some degree, yet people whom he hated and saw as a blight on society fall deeply in love with his work, much more so than people who agree with him (if only privately). Many people from all walks of life justify enjoying Lovecraft by trying to downplay the racism and classism of his work while others insist that he changed late in life. This feels disingenuous. My love of Lovecraft is not contingent on a loophole where it’s technically okay to read his work, and not acknowledging his bigotry only leaves me vulnerable to unconsciously absorbing it. I have no choice but to engage with the work critically rather than passively. Ignoring the flaws of his writing that come from his flaws as a person doesn’t make the work better or more enjoyable, it just limits one’s own ability to enjoy it honestly.

I’m a little afraid that someone who truly loves Bendy as much as Pastra does will see the patterns outlined in this article and feel like they aren’t allowed to enjoy the series anymore, or that they’re a bad person for not condemning it, or that they’re stupid for not seeing problems that someone else saw. I don’t want to make you think less of something you love, just more about it, to quote one HBomberGuy. By forcing myself to engage critically with the series in order to write about it, I found things I appreciated more than I realized. It would be a bad thing if I ended up convincing someone that Bendy isn’t worth loving because of gripes I have with the series. You don’t need me to tell you that you’re not a bad person for liking Bendy, but if there’s any doubt: You’re not a bad person for liking Bendy.

Perfect art would be impressive but leave us very little to chew on. Being able to engage with the flaws in media, letting it challenge us in ways beyond what the writer intended, is a very important part of growing as an audience member. People still engage honestly with Harry Potter even knowing the flaws of the writer and how the series echoes her personal failings, and we can say the same thing about H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos or Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game.

Bendy doesn’t have to be different. Joey Drew sputters about redemption, but the beauty of the series isn’t skin-deep whitewashing of past mistakes. Whether or not the creators gave the series a soul, fans do.

Inna Final Analysis

“Belief can make you succeed. Belief can make you rich. Belief can make you powerful. Why, with enough belief, you can even cheat death itself. Now that… is a beautiful and positively silly thought.”

Appearances matter. Not physical appearances, obviously, but public perception certainly does. As a series, Bendy is all about the ugly truth of the abusive workplaces that make our media. The cutesy ink demon is a monster terrorizing employees who are consumed by their own work. It’s a brilliant metaphor. The creators understood how impactful that imagery is, so they did their best to hide and cover up evidence of their own wrongdoing so that people wouldn’t look at them the same way.

It didn’t work.

“I will never shame or be upset at others being fans still,” Amber told me, “but I personally can't stand seeing the awful owners of this series prosper with no backlash or justice to the pain they've caused.”

Kindly Beast is still producing Bendy games under the name Joey Drew Studios. Bendy: The Cage is a followup to The Dark Revival intended to release in "2024", but so far all we have is a concept trailer and a few screenshots from the steam page. Of the three I spoke to, only Amber had heard of it, but she knew even less than I do. It’s set during the events of The Dark Revival as a side-story, meaning that it may struggle to onboard new players who won’t know the lore going in. At the same time, it would feel naive to assume that the company is desperately gasping for air as it’s dragged down into irrelevancy; the series is good at drawing people in even if the creators don’t understand why. As for the development process itself, there’s no word yet on if the company has started ritualistically sacrificing their remaining employees to the gods. The only thing we can say with absolute certainty about The Cage is that it will definitely get done “good enough” and that they may, eventually, acknowledge the fact that bugs exist.

Even though the series has some interesting things to say about abusive environments, how people in power see the world, and historical revisionism, the company behind it has no depth. The creators’ obsession with appearances manifests in a regressive attitude toward character design. Mike Mood insists that they only create characters to serve instrumental function, but this idea that sexuality, race, or gender can only serve a narrative device just furthers the idea that people are white men by default, if only through process of elimination. And the games, at least, do nothing to explore the discrimination that people of that era faced in media production (or in general) despite it being right in line with the deeper themes of the series.

Body horror is poorly utilized in the games because the creators do not make a distinction between the instinctive fear of mutilation and the learned beauty standards that result in people being othered for their appearances. As a result, they fall into the trap of insisting that good people are pretty while “ugly” people are cruel. This too could have been subverted, incorporated into larger themes of appearances and truth that the series grapples with, but it was not.

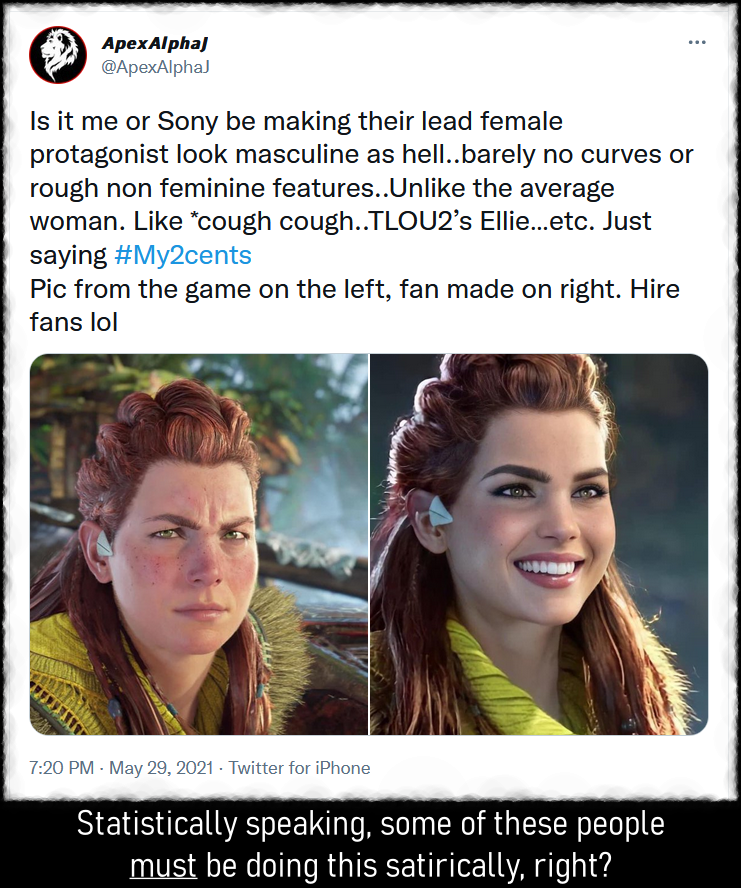

It’s tempting to pat ourselves on the back for implying that this is an isolated problem stemming from specific creators. I have never seen anyone talk about how Bendy does this, to the point I doubted my own observations. On some level, we’re ready to passively accept this and only really notice it when it’s hilarious, such as putting an attractive actress in glasses and frizzy hair to make her “the plain one” in need of a makeover.

Or when people proudly admit they’ve never seen a woman who wasn’t wearing “it’s literally my job to be in front of a camera” makeup.

When I asked Joe what he thought about my thesis, about physical appearance being used as an indicator of how categorically good or evil these characters are, he was skeptical. “I wouldn’t know the true intentions of the creative team, but to me, it doesn’t really feel that way, at least not intentionally. It has been a common trope since the dawn of animation to depict bad guys with scruffy-looking features, scars, ugly, and all those negative features. I think the creators utilized the same trope to design their characters because honestly, it’s the norm still.”

He’s right. It’s still the norm, and it would hardly be fair to pretend that we’re talking about a leaky pipe when the whole roof is dripping. The creators are responsible for their product, but they didn’t create the environment where this kind of practice is standard.

There isn’t really a solution for this. I like me some finger-pointing as much as the next gossipy hen, but it’s not enough to tell creators to “do better.” Public calls for accountability turn into harassment campaigns as often as they don’t, and assigning blame to the fans isn’t a satisfying alternative. Ultimately, the thing most worth taking away from this is that as consumers, we only get smarter by both consuming flawed media and engaging honestly with it. We don’t have to perpetuate those flaws in our own work, but we can’t settle for demanding perfect media.

That too, I think, would be a little vain.

All images taken from the Bendy Wiki

This article took two more months to finish than it was supposed to because I just had too much to say. If you'd like to throw a bit of change my way to show support, you can donate as little as a dollar to my ko-fi. It all makes a difference.